Dans le cadre des 12ème assises internationales du Journalisme de Tours, le collectif #Payetoiunjournaliste a proposé de donner la parole aux citoyens sur la question …

L'œil de la Maison des journalistes

Liberté d'informer & Accès à l'information

Dans le cadre des 12ème assises internationales du Journalisme de Tours, le collectif #Payetoiunjournaliste a proposé de donner la parole aux citoyens sur la question …

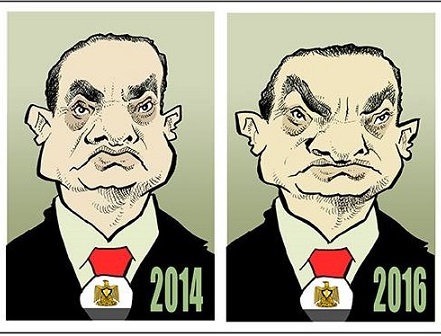

Ranked 161st in the World Press Freedom Index 2018 from Reporters Without Borders, contemporary Egypt is characterized by a rapid deterioration in press freedom, subject …

In the first two months of 2019, the Afghan Media Community lost three of its members in two successive incidents. Javid Noori, a radio journalist, …

On February 3, 2019 the Egyptian parliament proposed a series of constitutional amendments that would involve most remarkably an extension of the presidential limit mandate, …